Post by Mauricio Miranda.

Bogota will try to learn from one of the most successful urban cable car stories by attempting to emulate Medellin’s achievements.

Residents in Colombia’s capital city still encounter shockingly long and uncomfortable commutes despite the extensiveness its world renowned TransMilenio BRT system.

But if there has been something that we have advocated here at the Gondola Project, it is the belief that no technology is a cure all solution for all transport challenges — especially when a major urban center has nearly 8 million residents.

Bogota seems to be in the extremes of the spectrum in terms of urbanism and mobility — the city has probably been praised as much as it has been condemned. Former mayor Enrique Peñalosa and true urbanism enthusiast (the man who also advocated for TransMilenio) was able to retake sidewalks from parked cars and convert them into vibrant public spaces.

The pedestrian experience improved and so made way for the expansion of sidewalks and the construction of more than 300 km of bikeways in the whole city. It is such an important mobility feature in Bogota that every Sunday, major avenues are closed for bikes, roller bladders, and all non-motorized means to take the street and enjoy the city in a healthy and fun way.

These changes came more than fifteen years ago. The population of Bogota then was near the six million mark; today there has been a 25% increase. Unfortunately since then no major transportation projects have been built. And if you ask anyone (driver or transit user) what their commute experience is, there is just one answer — sheer chaos.

This is a problem that is citywide and it affects every single citizen. However, lower income residents have an even tougher time trying to travel to and from amenities, especially because they live on the hillsides where much of the transit service is inaccessible or inconvenient.

The local government was determined to solve this particular problem and has decided to follow Medellin’s footsteps by introducing two cable car lines in these marginalized areas. This comes as result of the realization that given the large size of the city and its different topographical characteristics, an integrated system of different technologies must be put in place — BRT, HRT and of course Cable Propelled Transit (CPT).

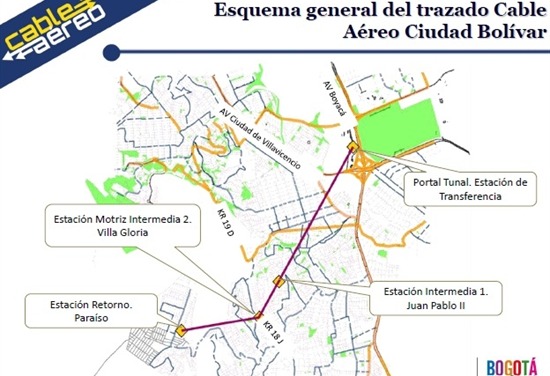

Between the two ‘CableBogota’ (as it is currently is called) lines, the system will be 7.2 km in length, with 7 stations, 60 towers and have 38,000 square metres of public space. The first line is referred as the Ciudad Bolivar line, and the second is referred as San Cristobal. These lines are saving on average more than two hours daily on commuting to the riders affected.

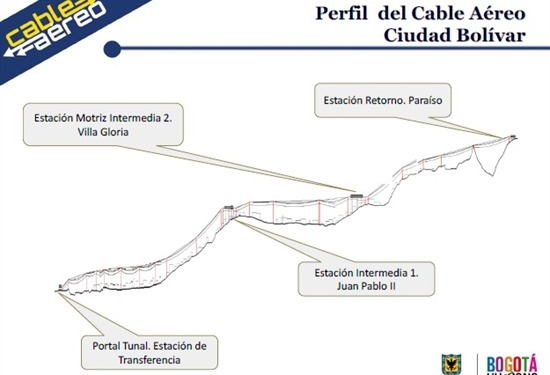

The travel time from the Portal Tunal to Juan Pablo II is 7 minutes; to Villa Gloria is 11 minutes; and El Paraiso is 15 minutes – having a total round trip time of 30 minutes. The line will have 24 towers along the four stations, and between the Juan Pablo II and Villa Gloria stations there will be a 130-degree angle turn. The system is expected to move 2,600 pphpd at peak hour.

The construction of the El Paraiso station is also meant to be a limiting landmark of urban growth, and so no more future informal settlements are considered to be in the limits of Bogota.

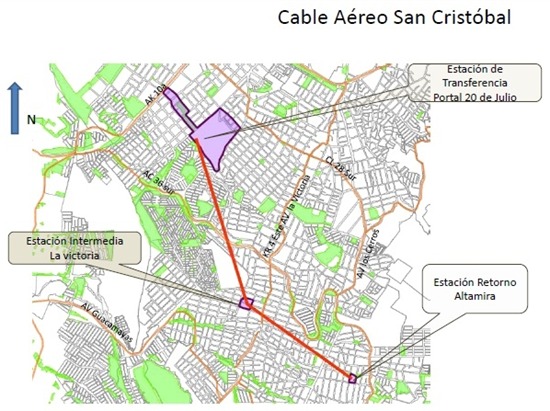

The San Cristobal 2.8 km line will start from the Portal 20 de Julio, another southern end of the TransMilenio network. It will go on to the intermediate station of La Victoria, and finishing up on the Altamira station. There will be 22 towers and 100 cabins that will serve the 2,700 pphpd that will use the system at peak hour.

Travel times are very encouraging as it only takes 8 minutes from the Portal 20 de Julio to the La Victoria station, and 3 more minutes to the Altamira station; having a total round trip time of just 22 minutes.

Just like in Medellin, the Bogota Cable Car lines will be connecting to its main transportation system, TransMilenio.

Metro Medellin has been very proactive in advising Bogota on how to take advantage of the opportunities for improving the urban fabric that having a system like this offers. The stations of both lines are meant to be either an entertainment or social hub for all citizens, having planned schools, infrastructure for social security, water features, pools, libraries, etc.

The public input has been fundamental on this project. Every public space that will be constructed comes from the proposals of organized neighborhoods committees on how they think the space that they will be using is best used by their communities.

The Ciudad Bolivar line is expected to be completed by November 2015, and the San Cristobal line will be open to the public on February 2016.

Every person in Bogota is hoping that these initiatives will one day put the city at the same level as Medellin in terms of transportation – or at least close to it. Medellin has completed exemplary work in many fields, but it has excelled particularly in urban transportation and social justice (mainly thanks to the MetroCable). Medellin has done so well that it was recently named as the best Latin American city to live in.

However, it is important we recognize that not all cities are the same. As such, decision-makers must understand that one cannot merely copy a plan, port it over and expect the same results. Nevertheless, Bogota seems to have the necessary ingredients for a successful CPT system: topographical variations, extreme automobile congestion, limited finances and a poorly integrated public transit network.

It will be very interesting to see how this transportation master plan improves mobility, and how much of an effect it will have on people’s perception of the city. Bogota lacks a sense of ownership and lacks cohesion in many ways that are unseen. However, an integrated and multi-modal transit network has been a game changer to many of these cities in similar conditions, and my guess is that it will do so once again.

7 Comments

Great insight into Bogota’s Cable Car. I’m just surprised it took them this long to decide to follow in the footsteps of Medellin.

I think there’s a typo, “38,000 square km of public space” I’m assuming it’s square metres not square km?

Great article BTW!

good catch sam. thx!

@PeterK Unfortunately for the past 10 years (and even today) there has been a very unstable body of public administration, and as you can imagine these projects become highly politicized – pretty much just waiting for the green light. Hopefully they keep to the deadlines and we’ll see these cable cars up and running before 2016.

“Waiting for a green light”? Bullshit (sorry). The first Detachable Grip Gondola of Medellín amortized within 8 months, they sold/sell carbon dioxide allowances, they tapped into a goldmine ! ! ! And now they make money with a fully paid ropeway. This is one of the reasons, why Medellín now is erecting up their third line and Bogota wants two of them and so many people/cities are completely crazy about it.

@Guenther This project has been on the agenda of city council for years now, but it has been a struggle to get it going – mainly because of the public and political pressure of having a HRT system as a priority. It hasn’t helped either that the new official plan has been delayed multiple times because of their inability to reach consensus, stoping the development of not only the cable car project, but any major infrastructure initiative.