A long time ago we asked the question When is a Minute, Not A Minute? In that post we went into how one’s perception of travel time is relative to how they’re actually travelling. As we note in that post, the Transportation Research Board states that a minute of time waiting for a transit vehicle is equivalent to 2.1 minutes of in-vehicle time. This figure increases to 2.5 minutes at transfer points.

This suggests some very interesting things about how wait times have an impact on transit ridership and how we might be able to play with them to increase ridership.

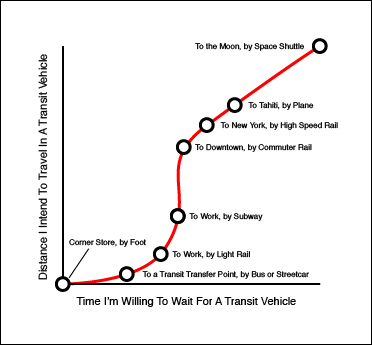

That stats always rolling around in the back of my head, and I’ve recently been playing with a similar idea for the last couple of weeks and I wanted to get our readers’ reactions and comments to it before I put together a “final” version. Remember, this is very rough and preliminary:

The basic idea here is that the time we’re willing to wait for any given transit vehicle is dependent upon the time we’re likely to spend travelling a given distance on that vehicle. The longer (further?) we’re going to travel by that mode, the longer we’re willing to wait.

While by no means mathematically precise, I think it’s anecdotally and intuitively correct: We’re willing to spend 3 hours waiting at an airport for our plane to travel literally thousands of kilometres, but we’re only willing to wait a few minutes for a bus to take us a few klicks to a subway station.

There are, I suspect, some large implications for this, but I’d rather save those until I get some reactions, corrections and ideas from everyone else.

16 Comments

I think what’s missing in this equation is how often vehicles come as well as if they keep to their schedule.

First of all, since I know subways generally run every 5 minutes or so, I’m not expecting to wait as long as the chart indicates. I also don’t think the distance I travel on a subway, bus, or streetcar is all that different — for me at least. I choose the mode by which will get me the closest to where I need to go.

The issue of high speed rail, commuter rail, and plane is completely different. If I know when the train will arrive, there is no need to get there way ahead of time. If anything these two are the modes where you could time your trip most easily. At the same time, people may be more inclined to arrive early because of the frequency of the vehicles. If I know a streetcar runs every 10 minutes, but a commuter rail is on the hour, I’m definitely more concerned about catching the commuter train.

As for a plane, that’s a matter of everything from cost, frequency, check points, baggage, and lines. If these steps were required for buses and subways, everyone would drive.

I think the question is how WILLING are you to wait for a given mode to get to get to a specific destination. The way I broke things up was by the general usage of each mode. The longer the distance to travel, the more “robust” a technology we’re looking at.

For any public transit system to work efficiently, I would say that wait times should never be greater than 5-10 minutes.

Especially in a society built on instant-gratification and automobile dominance, this will be difficult if not impossible. People get frustrated just waiting 2 seconds for a website load on their smartphones.

I honestly think that the whole concept of public transit in North America won’t work efficiently unless two critical things happen here. 1) The cost of owning your own vehicle becomes out of reach for a regular citizen. 2) Suddenly pour billions into building more true rapid transit lines (subways, exclsuive LRT/BRT etc).

For one thing, although a decrease in automobile dependency is often seen as a positive, too much of a decrease in automobile dependency in North America worries me as it’s partially a reflection of a society’s innate purchasing power.

with surmounting debt and high unemployment and under-empolyment in the US, the option for owning a car is steadily becoming out of reach for many, especially young people. the time to build public transit is now.

Too bad the government is also in debt so no public transit either =(.

Big problem.

3) We remove density limits in cities.

The world is urbanizing, but there’s so many old bad rules in US cities (I assume Canada has a few as well) that limit heights, require parking, require setbacks, etc., that we’re pushing people into the suburbs that would prefer city life.

You need density for good transit. And with high enough density you don’t even need transit to get around.

I think what we do in North America is say you can have hyper-density (in the form of Vancouver, Toronto or Seattle condos) or you can have hyper-suburbanization. We rarely have a nice middle ground of 4-6 storey walk-ups, brownstones or town homes.

I’ll go by personal guts on Swiss standard on this one…

5 minutes for bus, at transfer station

10 minutes for bus, at roadside

5 Minutes for LRT/Subway

15 Minutes for Local Rail

30 Minutes for Intercity/High Speed

Also dwell time feeling is impacted highly by the display of the next vehicle arrival information, this is clutch.

Also, scheduling everything transit to a tee and holding that schedule as priority over other modes of transportation is clutch as well.

But try and link that to how long a trip you’re planning on taking. And again, it’s a question of how long are you WILLING to wait rather than how long you actually wait.

This one is tricky. I think your graph is fine, as a qualitative graph (though a little tough to figure out). But the data depends what you’re asking, and to whom. Do you have a car? Is there parking available at your destination? Traffic on the way? Do you live on a hill? Is it snowing? I can ask a dozen more questions that would strongly affect this chart.

If you survey a given population, then you might get reasonable data. But that data will still be affected by these questions – if the survey population lives in a very cold and windy climate, they may be less likely to stand on the street for a long time waiting for a bus. If the survey population has very low car and bicycle ownership, maybe they’ll wait longer because they have no other choice.

It’s a conceptual idea and one I’m still working out. See David’s comment and my reply to it.

As a heuristic, my wait times closely matched what Christian wrote.

I’ve always felt that understanding the randomness of a transit vehicle arriving on schedule is a strong factor as well. It’s fine to know the schedule of your options, but if you know your vehicle can be as much as 5 min early or late, that implies you are willing to wait at least 10 minutes.

To take that to your transit vehicle wait time vs total transit time; If the randomness of waiting is a large percentage of the total commute, this tends to penalize the short-hop type modes such as buses and subways. The long-distance trips such as planes, high-speed rail might have a vehicle wait variation of 10 -20 minutes but this random wait (as opposed to known wait) is small compared to the whole trip.

That’s what I’m getting at exactly, David. (Thanks for joining the conversation!)

The issue I’m seeing is that we likely make an implicit (and likely unconscious) comparison between the total trip time vs. the total wait time. It would be absurd to wait 10 minutes for a 5 minute bus ride as we know intuitively that we could walk that distance in less time than 10 minutes.

What interests me is this: Have we made a colossal error by making our trunk lines perform with short wait times, even though they’re the lines people are most likely to travel the greatest distances? And while I’m not sure if that could be called a “colossal error” I’m certain that the long wait times that characterize feeder systems into the trunk lines are indeed an error that few people have looked at.

Thoughts?

“Have we made a colossal error by making our trunk lines perform with short wait times, even though they’re the lines people are most likely to travel the greatest distances?”

Probably no… It would be interesting to separate the short wait times (aka frequent service) from simply moving more people on a single vehicle. Be it BRT or rail, trunk services move the most people so need the most vehicles, hence shorter time between vehicles.

I’m certain that many a transit provider has attempted more frequent feeder service, but passenger volume doesn’t dictate that. Additionally, trunk systems are transfer reliant and have a heavy wait penalty over waiting to start a trip; a traveller doesn’t want to multiply their waiting to transfer to the trunk when they all ready did so to start the trip.

Agreed. So let’s not sacrifice short wait times at the trunk, but let’s contemplate the wait times for the feeder. Because if we can’t get people to the trunk, then short wait/transfer times is irrelevant.