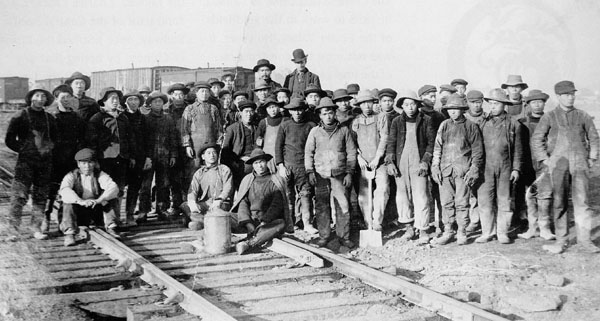

A Chinese work gang for the Great Northern Railway, circa 1909. Source: Beyond the golden mountain. Via Library and Archives Canada.

Last week, the New York Times ran an interesting debate between several economists and urban scholars regarding the place and future of High Speed Rail in America. Generally speaking, the two sides that emerged from the conversation are as follows:

- CON: High Speed Rail (HSR) is expensive and too risky. Americans drive (a lot) and they are unlikely to switch to HSR. Taxpayers will be left on the hook for both capital and operational expenses.

- PRO: We can’t afford not to build HSR. Emerging mega-regions require high speed links within them.

Frankly, I have no opinion on HSR. Like all other transit modes and technologies, the merit isn’t within the technology itself. High Speed Rail isn’t latently good. Rather, the technology’s merits shine through when implemented in an environment where it makes social, environmental and fiscal sense.

Whether America is just such an environment isn’t for me to say.

Robert D. Yaro – one of the debate’s participants – does, however, believe America is just such an environment. Yaro is the President of the Regional Plan Association and is a professor of planning at the University Pennsylvania and had this to say about High Speed Rail:

“Throughout history, our nation’s leaders championed federal investments in infrastructure. Washington led efforts to build canals right after the Revolution, Lincoln led efforts to build the Trans-Continental Railroad during the Civil War…”

This is a not uncommon argument used in support of HSR. It’s a compelling, emotional argument because it invokes Lincoln and the can-do American spirit that helped propel that country to the forefront of the world. It also ignores a key part of the Trans-Continental Railroad’s history; it was built in great part by Chinese immigrants who were systematically abused and exploited:

“The Central Pacific’s Chinese immigrant workers received just $26-$35 a month for a 12-hour day, 6-day work week and had to provide their own food and tents. White workers received about $35 a month and were furnished with food and shelter. Incredibly, the Chinese immigrant workers saved as much as $20 a month which many eventually used to buy land. These workers quickly earned a reputation as tireless and extraordinarily reliable workers–“quiet, peaceable, patient, industrious, and economical.” Within two years, 12,000 of the Central Pacific railroad’s 13,500 employees were Chinese immigrants.

The work was grueling, performed almost entirely by hand. With pickaxes, hammers, and crowbars, workers chipped out railbeds. Dirt and rock were carried away in baskets and carts. Tree stumps had to be rooted out, tracks laid, spikes driven, and aqua ducts and tunnels constructed.

To carve out a rail bed from ridges that jutted up 2,000 over the valley below, Chinese immigrants were lowered in baskets to hammer at solid shale and granite and insert dynamite. During the winter of 1865-1866, when the railroad carved passages through the summit of the Sierra Nevadas, 3,000 lived and worked in tunnels dug beneath 40-foot snowdrifts. Accidents, avalanches, and explosions left as estimated 1,200 Chinese immigrant workers dead.”

Source: Digital History

Canada – Northern cousin to America and never one to shy away from a importing a good deal from their southern neighbors – meanwhile, wanted in on the action and did virtually the same thing:

“Between 1881 and 1884, as many as 17 000 Chinese men came to B.C. to work as labourers on the Canadian Pacific Railway. The Chinese workers worked for $1.00 a day, and from this $1.00 the workers had to still pay for their food and their camping and cooking gear. White workers did not have to pay for these things even though they were paid more money ($1.50-$2.50 per day). As well as being paid less, Chinese workers were given the most back-breaking and dangerous work to do. They cleared and graded the railway’s roadbed. They blasted tunnels through the rock. There were accidents, fires and disasters. Landslides and dynamite blasts killed many. There was no proper medical care and many Chinese workers depended on herbal cures to help them.”

Source: Library and Archives Canada

When people like Mr. Yaro invoke North Americans’ ability to historically tackle huge problems and build massive projects, they conveniently fail to include this detail. It wasn’t Americans and Canadians who bravely conquered the wild and built railways that would unite their countries and help them prosper. It was the Chinese. And for their efforts we underpaid them, discriminated against them, and were indirectly responsible for killing a few thousand.

I bring this up not out of political correctness or white guilt. I bring it up to point out the very different economic realities that existed 100 years ago.

100 years ago you could treat people like slaves and cattle and that’s how you got things done. You could put children in mines underground and if it collapsed on them, oh well – that was just the price of doing business. Paying manual laborers was practically optional. Adjusted for inflation, the $1.00 a day quoted above is equivalent to roughly $25.00 today – and that was before costs for food, clothing and shelter were deducted.

Infrastructure is easy when the workers are happy to toil away in the hell of your steel mill or subway tunnel instead of the worse hell of their abandoned homeland. It is quite fair to speculate, I think, that without this cheap and expendable labor, many major infrastructure projects would never have been completed.

When we invoke these historic projects to justify things like High Speed Rail networks, we forget that we accomplished what we accomplished only by riding roughshod over the rights of many, many people. Remember: Minimum wages are a fairly new phenomenon in human history.

When we point to countries like China and the UAE and proclaim “if they can do it, then so can we!” we don’t acknowledge that they’re accomplishing what they are by doing many of the same things we once did. China is a human rights disaster and Dubai is no angel either (check out Human Rights Watch’s report Building Towers, Cheating Workers).

Do I long for a time when railroads and subways were actually built quickly and efficiently? Sure, but not at any cost. Our economic reality has changed. And until we are willing to find new ways to drive down the cost of mass infrastructure projects (that don’t trade in the exploitation of human misery and suffering), invoking our past infrastructure glories is dishonest, disingenuous and wrong-headed.

After all, we didn’t build the railroads. We outsourced them to China.

8 Comments

Well that was depressing, but also thought-provoking.

I guess I would wonder if higher labor unit costs are really all that problematic these days, meaning they are the primary source of prohibitive infrastructure project costs, given labor-productivity gains. Or, in other words, haven’t machines largely taken the place of exploited human workers? I don’t know, but I’d like to get some answers before conceding that the lack of slave labor really is a fundamental impediment to ambitious infrastructure plans.

Brian,

Glad I could depress you (I think). Tunnel boring machines are expensive. Very expensive. If you look at Toronto’s new subway extension, it utilizes tunnel boring technologies and the line will still be $200 – $300M per kilometer. Someone’s got to build, engineer and maintain the vehicle. And while tunnel boring machines are indeed useful, they are not fully-automated. You still need scads of people to operate them and finish the tunnel.

I don’t know what to say. Writing that post depressed me, too, but I thought it needed to be said. I don’t believe the “lack of slave labor” to be the sole impediment to our infrastructure plans, but I do think it contributes greatly. Obviously we could never return to such a state. So the challenge then is how we find another way.

In Countries with cheap labor manual labor is still favored in countries with expensive labor machines are preferred. I regularly visit construction side over the world. If you are in a rich country a crane will lift material in a developing country manpower and pulleys are used if it is possible. Of course the crane can lift all the things in a couple of minutes while the rope and pulley system needs much longer. But it is cheaper than hire a crane. The 25 USD per day is realistic in many countries in the world. The rent of even a small machine is much higher. Another example is pulling of electrical cables either use a special cable pulling machine ore use a group of workers. The advantage is that the work crew can pull cable on one day and paint something another day. Machines are very specialized.

Stations contribute to the high cost with subway. The material to excavate a station is equivalent to some kilometers of ordinary tunnel track plus there are many entrances and many subway station also act a street underpass and underground shopping center. Thats why most new subways us automated trains now. This cuts station length in half while having the same capacity.

I realize the relevant machines can often be very expensive, but of course that cost has to be spread out over all the work they do. Generally, in many industries we have seen the replacement of a lot of cheap unskilled labor with expensive machines (which has also involved some remaining higher-skilled and higher-paid jobs), and yet unit production costs have actually gone down, not up. So while maybe there is something inherent to infrastructure projects that would make then an exception to this overall industrial trend, I think that is a case that has to be made with some numerical rigor.

Speaking of which, this article and the associated comments gets into why Spain’s subways are costing so much less per mile than U.S. subways. One possibility mentioned in the comments is that perhaps the Spanish are using the same tunnel-boring machines to do more miles each, which would reduce the per-mile machine cost. There is also a lot of discussion there about the possibility of problems in design, contracting, and so on. And indeed some people have suggested it is unit labor costs, but I don’t see much evidence presented to back up that thesis.

So, I’d still like to see hard numbers backing up the claim that the absence of cheap unskilled labor is a highly significant contributor to higher costs for large-scale infrastructure projects. I’m not saying that is impossible, just that it isn’t obvious that should be the case.

Brian,

I think you forgot the link to the article you mention. Do you have it? It’d be great to read.