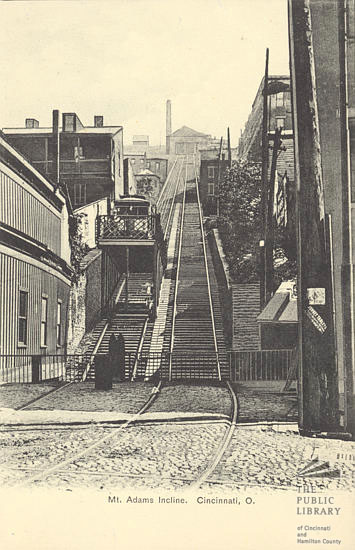

The Mount Adams Incline in Cincinnati, Ohio

Way back in the day (we’re talking 1872 here) Cincinnati, Ohio was clustered at the base of several small mountains. As the city grew and expanded up the sides of the mountain city officials had a problem: How were people and goods to be moved up and down the mountains?

This was, of course, before automobiles. People were still using horse-and-wagon and the steep grades surrounding Cincinnati threatened the city’s growth. A series of five inclined railways / funiculars were used to ingeniously solve this problem.

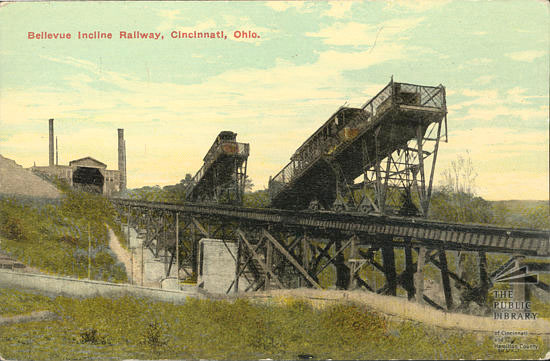

Bellevue Incline in Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati’s funiculars were remarkably unique and simple in concept. As far as I am aware (and that could change), I believe they were almost entirely new for the time. And as such, I think they deserve their own classification: Let’s just call them “Cincinnati Funiculars.” for ease and simplicity’s sake.

What differentiates a Cincinnati Funicular from a traditional funicular is this: Traditional funiculars were (and continue to be) enclosed vehicles running up and down a mountain. A Cincinnati Funicular, however, was simply a gated platform that was relatively level to the horizon. It’s entrances and exits were aligned not with a sidewalk, but instead with the existing street grid.

A Cincinnati-Style Funicular; Cincinnati, Ohio

This pared-down design conceit allowed horse-and-wagon teams to move from the street below, onto the funicular, up the mountain and onto the street above with little trouble. As time passed, the system allowed streetcars, trolleys and buses to do the same. It was a rare situation of transit technologies co-operating rather than competing with each other.

So who cares, right? Transit planners and advocates should:

Almost all rail systems (that includes, light rail, streetcar and subways) are limited to their location by how steep they can climb. It’s a limiting factor they can’t avoid. Rail technology simply cannot climb more than a roughly 10 degree incline. This severely restricts their potential for installation in all but the flattest of locations (see Hamilton, Ontario for a modern day example of this situation). When partnered, however, with a Cincinnati Funicular, that problem is alleviated, thereby opening up all new avenues for rail-based systems.

Sadly, like most fixed-link transit in North America, Cincinnati’s funiculars were gone by 1948. Unlike rail transit systems, buses and private automobiles had no troubles ascending the mountains, thereby making the inclines redundant. The design concept of a Cincinnati Funicular was forgotten about almost completely and the funiculars were demolished.

But now, given that the gussied-up streetcar known as Light Rail is king again I have a feeling we’ll be seeing Cincinnati Funiculars sometime soon once more.

Mount Adams Incline.

Historical images of the Cincinatti Funicular are public domain. They can be viewed at www.cincinnati-transit.net.

Creative Commons images by JOE M500 and phototram

4 Comments

Love this post (I’m from Cincinnati). We Cincinnatians called our Funiculars “Inclines.” And we call our mountains “hills”! (OK, so Mount Adams is grandiosely call a Mount, but it’s really just a steep hill.)

I’ve been trying to “bring back the inclines” in Cincinnati for years now and finally am finding at least verbal support. Several city plans do or will mention inclines as transportation augmentation for the city, connector modes – but not, for now, to assist street cars (also being planned) to scale our “Mounts.” What I have proposed are smaller, lighter, less expensive funicular “inclines” to effectively level our challenging topography for walking and biking, moving people into hilltop neighborhoods for the day or evening entertainment without moving more cars at the same time, reducing parking congestion, air pollution and our carbon footprint. Likely something of a hybrid between the old open-platform Cincinnati Funiculars and what your site shows in Zurich (which moves people and bikes in enclosed inclined cable cars, free to ride sponsored by a local bank; I’d like to get Cincinnati’s Proctor and Gamble Corp., whose headquarters is near the original boarding site for the Mt. Adams incline, to sponsor our first one).

That’s great, William! Is there anything we can do to help the process?